TWHP

The Players:

John Mackay

James Fair

James Flood

William O'Brien

The Comstock Lode

The Greatest Silver Strike in History and the Big Bonanza

Mention of the California Gold Rush of 1849 often elicits the response that it wasn't the gold that made men rich, but rather selling supplies to the miners. And there is truth in that. But another pedantic response awaits that one: It wasn't the Gold Rush that made California rich, but the Comstock Lode.

Ironically, many emigrants to California found gold in the canyons on the Nevada side of the Sierras, but they ignored what they saw, believing that it couldn't be significant if others kept moving on. After it became evident that the best of the California gold deposits were gone, some miners filtered back to make a modest living off what remained in those gullies they'd passed by. Several years more creeped along before it occurred to anyone to assay the ubiquitous blueish sand and rock that kept interfering with the thin gold pickings. It proved to be rich silver ore.

Recognized finally in 1859, the Comstock Lode appeared to be a bottomless natural store of silver. While the disappointing realities of the Gold Rush encouraged most men to turn their efforts elsewhere after a few years, the silver bonanzas of western Nevada captured the world's imagination for the best part of two decades. Fortunes large and small enriched the lucky, the smart and the dishonest, and a frenzy of obsessive stock trading engulfed all classes of San Franciscan. Investors and money men from the world over schemed and manipulated for a piece of the action, and whole industries materialized to develop the mines.

Nevada's mountains were denuded of trees to provide timber shoring within the mines, and the forests of the Sierras were depleted for wood to fire the steam boilers running the machinery. Railroads were built to feed the beast, and so were miles of flumes, to deliver either water or timber where it was needed. Modern mining was invented along the way, and mechanics contrived gigantic metal contraptions of every description to work the ore: elevators dropping thousands of feet into the earth to deliver miners and supplies; stamp mills of titanic proportions to crush the rock; elaborate conveyor systems to transport it; mighty pumps to remove the water that kept seeping in; powerful compressors to provide power for drills and air to breathe.

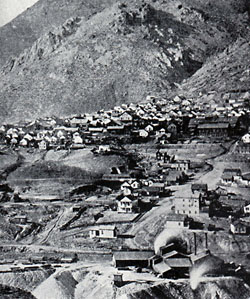

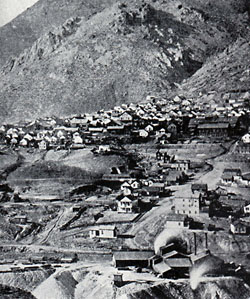

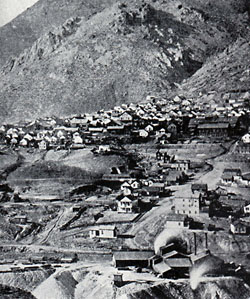

But Virginia City comprised the greatest wonder of all, a town of stunning sophistication and luxury clinging to the edge of Sun Mountain and overlooking a moonscape. Some 22,000 people came to live there during the most productive years of the lode, and they took turns working round the clock in the mines, saloons and brothels of a city that not only never slept, but never took a break either. It seemed to have a heart of its own as the stamp mills throbbed in unison with pumps and compressors to create the impression of a thing alive that occasionally belched from below with explosions, or screamed above, in a cacophony of steam whistles marking the beginings and ends of work shifts.

The finest food, drink and goods in the world could be had on the fringes of barren desert, and the International Hotel accommodated the wealthy and powerful from across the continent and beyond who came to see the stupendous happenings. Tycoons and dignitaries of every sort arrived in private railroad cars so often that they ultimately ceased to excite comment, and the mines ran so many tours underground that they developed special wardrobes and routines for the well-healed tourists, absentee owners and would-be investors. The contrasts among urban luxury, a hellish underworld and sun-baked desolation marked one of the marvels of the age.

San Francisco controlled the lode with an imperial disdain, and its men of finance fought like generals to vanquish their enemies and plunder their riches. They worked every angle, fair or foul, to have their ways. They salted mines, they issued false reports, they bribed reporters to publicize them, they created rumor campaigns, they sued each other and they bought government.

So compelling was the silver fever that San Francisco itself began to suffer since every available penny chased mining stocks, while more conventional investments went begging. Banks had no extra money to loan to local business, and recession ever-threatened as more and more money poured into the holes in the ground that made many rich and many more destitute. People mortgaged their homes to buy mining stocks, and failed investments sent numberless souls to the grave through despair, alcoholism and suicide.

Meanwhile, the costs and challenges of raising tons of rock from thousands of feet in the earth kept the operations on the brink of disaster. First, the cave-ins, that made it impossible to mine the silver; that was fixed by a framework of heavy, timber cubes, hollow building blocks to support rock faces. Then it was bad air, solved first by air ducts, and then compressors, as the holes went deeper. Then the water came, in such torrents that months of pumping could not catch up with the flow.

Adolph Sutro contrived the solution, a four-mile long tunnel going straight into the mountain that would link all the mines and allow drainage and the free flow of air. It would be able to save lives and improve working conditions and he worked like a missionary to spread the faith. It took him a dozen years to get it built, it worked just as it was supposed to, and it didn't make any difference; by then, the silver was all gone. And Sutro, a sincere man who believed in what he did, overcame tremendous odds to do it and got many others to believe and invest, sold out at just the right time--probably by coincidence--to make his fortune. His buyers suffered ruin.

William Ralston founded the Bank of California in part to take advantage of the opportunities just over the mountains in Nevada, and he went on to become San Francisco's greatest financier in the 10 years before his death in 1875. Before then, he managed to monopolize business at the Comstock Lode through his lieutenant, William Sharon, as shrewd an operator as ever walked the earth. But by the early 1870s, a quartet of canny Irishmen--two miners and two saloon keepers--got control of the richest mine ever seen and became the envy of the world.

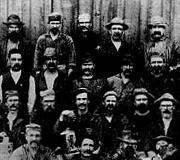

John Mackay, James Fair, James Flood and William O'Brien took over the Consolidated Virginia Mining Company, and by eschewing the lavish waste of other owners made their mine pay like no others. They became incredibly rich, and they entertained newspaper readers across the planet with their antics, their spending and, in some cases, their generosity.

They were known as the Bonanza Kings, but the title hardly did them justice; they had much more money than most monarchs.

By the early 1880s, it was clear that the end approached. The Comstock Lode began to die a slow death, with Virginia City not far behind. It now exists as a little tourist town a half-hour drive from Carson City, the Nevada state capitol. The legacy of the Bonanza Kings, however, lives on in San Francisco. The Fairmont Hotel on Nob Hill was built by James Fair's daughters, and the Pacific Union Club, across the street, started out as the Flood mansion. Down the hill, along Powell Street, the cable cars turn around in front of the Flood office building.

But the biggest legacy of all is to be seen across the West, between San Francisco and Chicago. The miners of the Comstock Lode took the lessons they learned along with all of their inventions back into the hinterlands further east, and set off subsequent mining booms anywhere there was valuable metal to be had. Whether copper in Montana, gold in the Dakotas or silver in Colorado, the mines fostered new towns and states and industries wherever they went.

Most of the mines are gone, and many of the once-thriving towns exist only as barely discernible outlines in the dirt, as piles of rubble, as clusters of rusting metals. You'd hardly believe anything of importance had ever happened in these desolate regions, let alone that they once fascinated peoples from Peking to Paris, from New York to New Zealand.

~ ~ ~